Skip to:

- Give Today

- Contact Us

- Media

- Search

News & Stories

Leadership Development Program

Professional Learning Program

Undergraduate Teaching Program

Common search terms

The

overnight release of the 2018 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and

Development’s (OECD) Program for International Student Assessment (PISA)

results confirms a continued decline in Australian student’s performance in science

and no improvement in reading and mathematics. Perhaps more significantly,

however, is the confirmation of a sustained gap in achievement between the most and least advantaged students, which

has remained relatively unchanged from 2015.

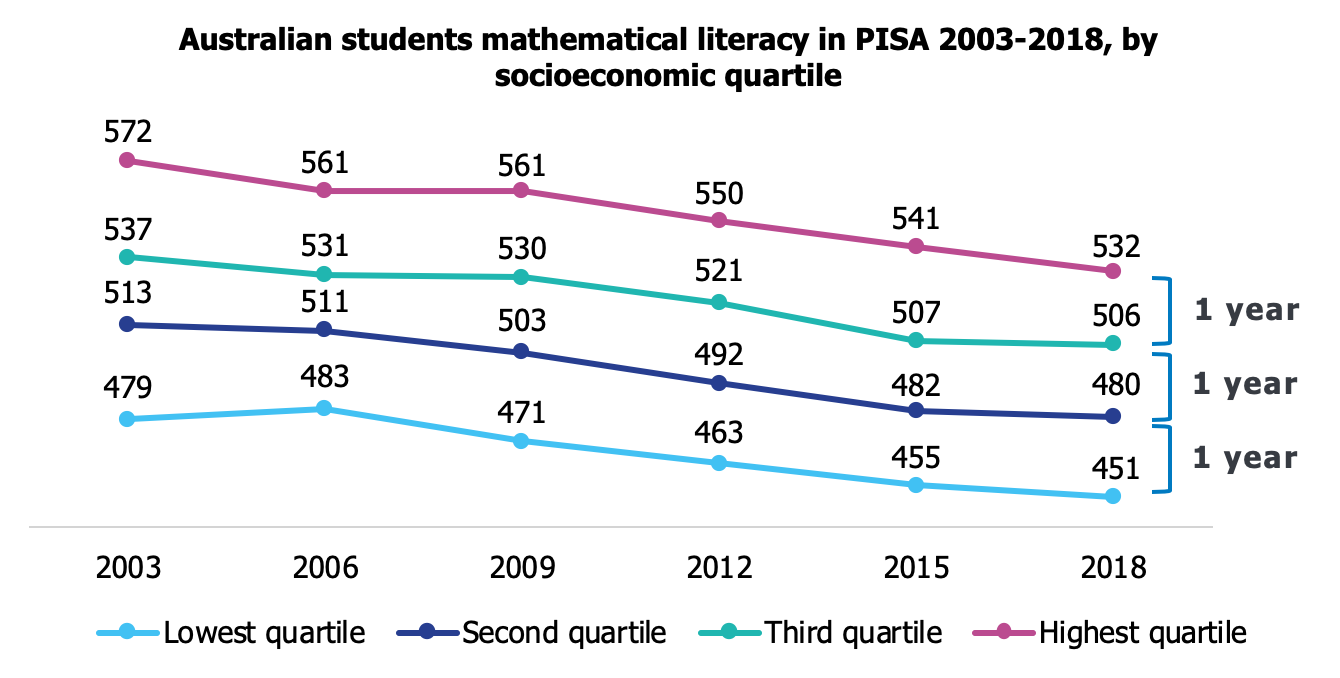

Students from the lowest socioeconomic quartile are approximately 3 years behind students from the highest socioeconomic quartile across all PISA domains. The difference in outcomes between socioeconomic quartiles for mathematics is approximately one year of schooling, a gap which has persisted for over a decade.

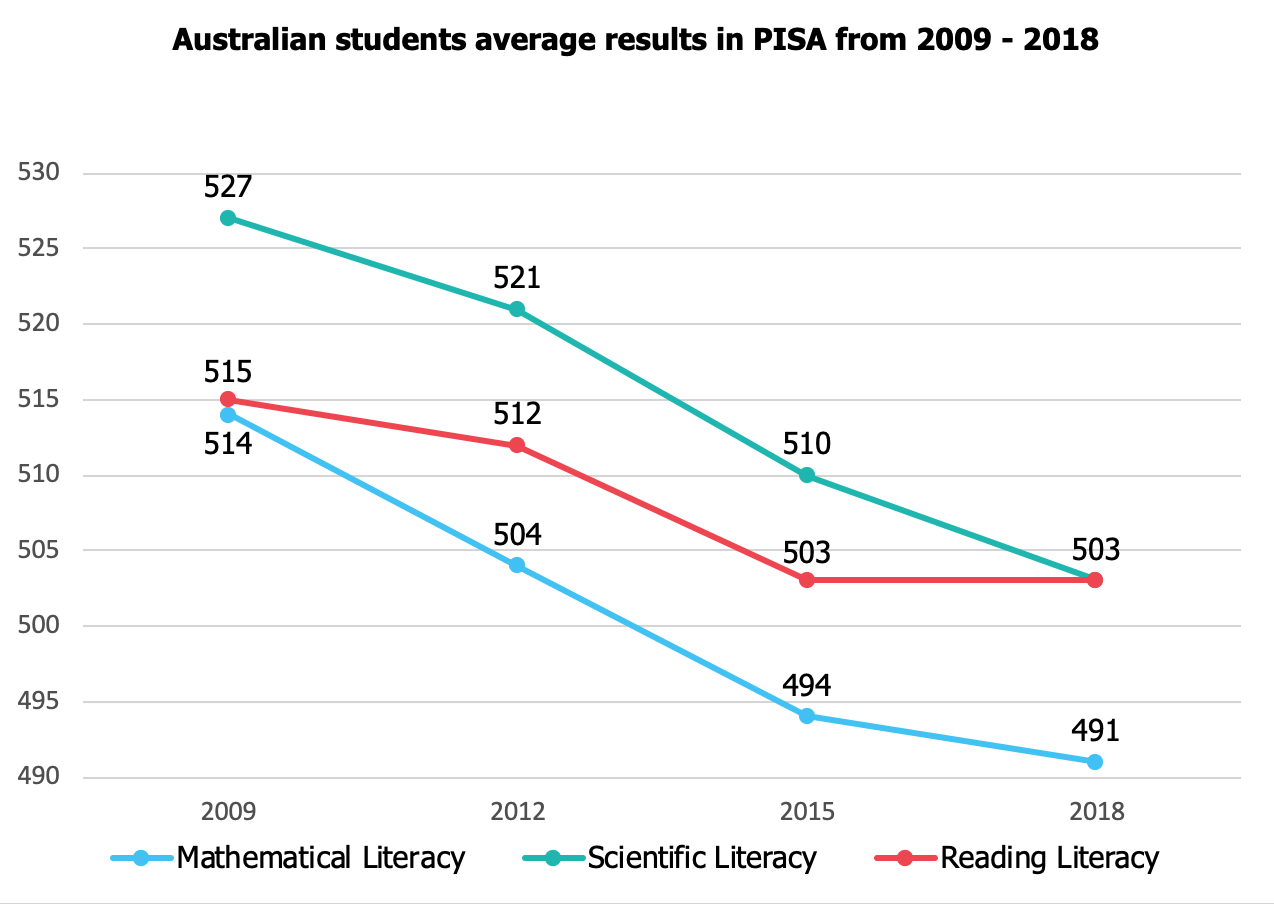

The 2018 results show a substantial decrease in overall achievement in just under 10 years, with students almost a full year behind those of the previous decade in all domains. This extends a downward trend that has been relatively consistent across all PISA domains since the testing began in 2000.

The sustained

decline in results since 2009 is due to the shrinking numbers of high

performing students and the steady rise of low performers.

In reading

literacy, for example, there has been a 5% increase in low performers from 2009

to 2018 and no change to the proportion of high performers.

As was true

for the previous round of PISA results in 2015, results vary significantly

between states and territories, but the most significant disparities in

achievement are found on the basis student background.

Australia’s

agreed national proficient standard for PISA has been set at Level 3 since 2015,

slightly higher than the international standard (Level 2), and thought

to represent a ‘challenging but reasonable’ expectation of student achievement

at age 15.

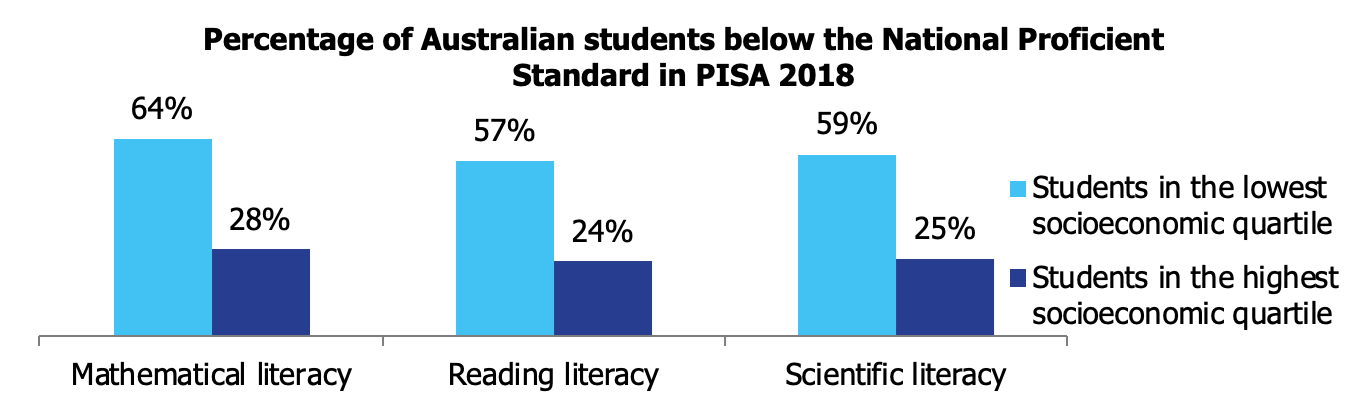

Around 41% Australian students fall below this national standard (an increase of approximately 10% from 2015), with those who are the most disadvantaged substantially less likely to reach Level 3.

Although

there is an increased proportion of students from all socioeconomic quartiles

failing to meet the National Proficient Standard, students from the lowest

quartiles are still two to three times less likely to reach Level 3.

Students in

regional and remote communities are also less likely to meet national

proficiency, with the average mean scores falling between 2 months and 2 years behind

their metropolitan dwelling counterparts.

Indigenous

students are still likely to be more than 2 years behind their non-indigenous

peers.

It is

important to recognize that disparity in achievement between these demographics

is not due to an innate difference in ability – with the right support,

students from disadvantaged backgrounds are able to excel.

The Mitchell Institute notes that despite the barriers that students from educationally disadvantaged backgrounds face, it is possible for students who have missed educational milestones to catch up.

As global workforces become increasingly flexible and mobile, PISA provides a useful point of comparison with neighbouring nations for policy makers, educators and service providers alike when considering if our students are set up for success and with the global community when investigating what works in improving student outcomes – particularly for those who are already disadvantaged.

Australia’s performance relative to other countries shows

our students are lagging behind the global leaders, the Chinese provinces of

Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang and Singapore, who are between 1 1/3

and 3 years ahead in equivalent years of schooling.

“The combined four provinces of China that participated – Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang – while by no means representing China as a whole, represent more than 180 million people, and have an average income well below the OECD average,” wrote Dr. Sue Thomson, national project manager for PISA, yesterday in the Conversation. “Their scores are about one and a half years of schooling higher than Australia in reading, three and a half years higher in maths, and three years higher in science.”

Australia ranks equal 13th in science (down from

10th in 2015), 11th in reading (down from 12th

in 2015) and 24th in mathematical literacy (down from 17th

in 2015 and, once again, performing no higher than the OECD average).

“We’re not giving [Australian students] the same level of skills as they are in other countries. That is a concern, particularly in a global economy where our kids will compete with kids all over the world,” Dr. Thomson continues.

The 2018

results also detailed several countries with a smaller range in performance

than Australia in each domain, including the high performing provinces of China

– indicating there is greater consistency of achievement within the region and

greater equity of achievement for students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

In a recent analysis report, Deloitte writes, “the economic, social and fiscal benefits of raising achievement levels among [disadvantaged] students are substantial, and justify additional efforts to improve learning growth across these groups.”

Teach for Australia (TFA), and a range of other dedicated organisations in the sector, work to address the disparity of achievement by partnering with communities who are in need. As the continued drop in results that this latest report illustrates, there is an increasing urgency for this work to be done.

At TFA, the

development of high quality teachers and school leaders is central to this

work.

“School leaders are crucial to delivering the change required to lift student outcomes in Australian schools. As leaders of learning in their school, they heavily influence their school’s culture, learning and pedagogical approaches, including the way the school maximises the learning growth of every student, every year.”

Australian Department of Education and Training, 2018

“Recognising, valuing and enhancing the teachers and school leaders with high levels of expertise makes the difference,” writes Dr. John Hattie, Professor of Education and Director of the Melbourne Education Research Institute at the University of Melbourne. “It’s what works best.”

According to Deloitte, “teaching practice is consistently found to be the most important in-school factor driving student outcomes.”

Australian Department of Education and Training, (issuing body.) (2018). Through growth to achievement : the report of the review to achieve educational excellence in Australian schools. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Education and Training.

Deloitte Access Economics (2019). Unpacking drivers of learning outcomes of students from different

backgrounds. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Education

Duffy, C.

and Wylie, B. (2019, December 3). Australian students behind in maths, reading

and science, PISA education study shows. ABC

News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-12-03/australia-education-results-maths-reading-science-getting-worse/11760880

Hattie, J.

(2015). What doesn’t work in education:

the politics of distraction. London, England.

Mitchell

Institute (authors Lamb, S., Jackson, J., Walstab, A. & Huo, S.). (2015). Educational opportunity in Australia 2015:

who succeeds and who misses out. Centre for International Research on

Education Systems, Victoria University for the Mitchell Institute. Melbourne,

Australia: Mitchell Institute.

Thomson, S.

(2019, December 3). Aussie students are a year behind students 10 years ago in

science maths and reading. The

Conversation. Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/aussie-students-are-a-year-behind-students-10-years-ago-in-science-maths-and-reading-127013