Skip to:

- Give Today

- Contact Us

- Media

- Search

News & Stories

Leadership Development Program

Undergraduate Teaching Program

Common search terms

What have I noticed?

Speaking my EAL students’ native language (Persian) has encouraged us to relate to one another as humans and connected us because of the similarities between our upbringings, cultural values and worldviews.

We celebrate the Persian New Year together, share food on different cultural occasions and discuss the implications of being EAL learners in Australia.

I have also taken advantage of these cultural and lingual similarities to assist students with more abstract concepts in the classroom.

Most recently this has included themes of sexism and violence in David Williamson’s infamous play, The Removalists. We explored how language is used as a tool of power to influence the powerless.

For students who have never studied these themes in any language, it is a huge help to explicate ideas in their mother-tongue with examples from texts, and recreate the process in English.

So why did this process not always go smoothly? Something was not quite right.

Some students were deemed ineligible for funding as the gaps in their demonstrated cognitive skills were labelled as an ‘EAL issue’.

Some have not done well in the ‘Program for Students with Disabilities Application’ because they simply could not articulate themselves in English.

Speaking with them and examining ideas in Persian, I keep noticing that schools could have mixed up the learning difficulties with being on the lower scale of the EAL Continuum and vice versa.

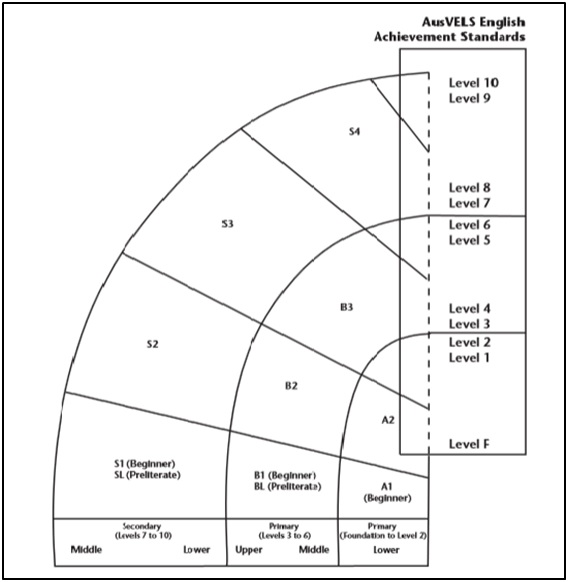

Image from PETAA

What have I looked up?

Through a quick search on the Victorian Department of Education and Training’s webpage, I saw that my school in is funded through a program called the ‘Student Resource Package’ (SRP). A portion of this (around 15.5%) goes to the ‘Equity’ funding to assist students who face challenges such as ‘difficult family circumstances, health or disability’.

I am not aiming at debating the suitability of the budget and distribution of the funding, as I don’t have the extent of knowledge regarding this matter. It was interesting, though, to notice that schools are responsible for determining eligible candidates for funding and proceeding with the formal application.

After discussing this with 4 other EAL teachers in the area, we found out we all had something in common. We could never recall being asked about students we teach every day. As their literacy teachers who spend the most school time with these students, the system has failed to involve us or keep us in the loop regarding their funding progress.

After more research, I realised that schools do occasionally use interpreters to assist students in the funding tests (e.g. in reading, writing, inferring, listening, analysing, recalling, etc.).

Interpreter availability, especially on site, is not always guaranteed in rural or remote areas. And when it is, I know from experience that an accurate translation of the examinee in these tests can be challenging – I was an interpreter in refugee camps around Australia for three years.

I previously worked with newly arrived refugees who had to undertake medical and mental health assessments. Not only did I have to pass high-stake national interpreting exams, but also consider all the cultural and social stigma around disability and funding.

There was a ton of pressure on me to remain culturally objective when interpreting in funding assessments.

There was also a lot of pressure on examinees as they expressed concerns on how their families, community and peers were going to perceive them.

This often resulted in them exaggerating their achievements and prior schooling due to the mentioned stigma, or completely lacking confidence in their knowledge and skills.

Why is this important?

Now I wonder how the Equity Funding bears the potential consequences.

Are we too quick to judge between cognitive and Continuum issues?

Do we use trained interpreters who work professionally and objectively to assist with the tests?

Do social and cultural values of the interpreter and student impact the test?

Are the tests specifically designed for EAL students, or mainly for mainstream students?

In the case of smaller towns, are the examinees comfortable with the presence of an interpreter whom they might know from their community and social groups?

I also wonder how having a teacher-aide in a classroom can impact students behind the curtains in their social and individual personas, and how I can, as a teacher curious to understand the limitations, minimise the inequity around it.

Now what?

I have seen students whose very legal rights of receiving cognitive, educational and moral support is being simply labelled as being ‘EAL’.

I ask myself how we can include teachers (especially EAL teachers, if relevant) to distinguish whether the students require purely pedagogical interventions, or if other adjustments are necessary.

I cannot also help but hope that the issue of funding is going to be communicated better to families, communities and students so that we can address the social stigma around it more effectively.

I have been brainstorming the possible solutions and also meeting with other EAL teachers in the region to raise this concern.

What we do know is that this issue deserves attention and we must reach out to experts and colleagues for that initial action plan, which could start from my classroom.

Hopefully analysing texts such as The Removalists will become more accessible for all students once I have some answers.