Skip to:

- Give Today

- Contact Us

- Media

- Search

News & Stories

Leadership Development Program

Undergraduate Teaching Program

Common search terms

Dr. Nick Irving is Senior Manager, Corporate Partnerships at Teach For Australia. Prior to moving into the not-for-profit sector, he was a lecturer in Modern History at Macquarie University in Sydney.

I think the moment I knew I was venturing into uncharted territory was when I transferred from the sleek Airbus at Perth International for the tiny twin-engined Fokker bound for Karratha. The faded plastic panelling of the overhead locker were tinted brown, whether with age or the dust of the mines I couldn’t tell. My travelling companions were markedly different as well. The bleary eyes of businessmen made dry by the transcontinental commute were replaced by boisterous, expletive-laden conversation, tan lines that would make a Bondi gym junkie quail, and tattoos that would have looked out of place on a Fitzroy street – but only just, and not in any way that was easy to make sense of. To my untrained urban eyes these were obvious signifiers of class, but beyond that coarse observation I was beyond my comfort zone. Which was fine, as the point of this trip was to learn – to watch and to listen, to admit I didn’t know what I didn’t know.

My first view of Karratha from the plane was the salt pans behind the Burrup Peninsula, with bulldozers digging up salt dried from seawater in the dry air and road trains full of salt threading their way along the long straight causeways. In topographical terms, little separated the tarmac from the endless flat earth beyond.

Once I was in the terminal building, the unmistakable flash of high-vis and the smell of bodies unwashed after hours of manual toil reminded me that I was in the land of the FIFO. It was Thursday afternoon and something of a changing of the guard was underway, with relatives of Karratha residents replacing the Perth-based workers flying home early for the weekend.

The high-vis continued into the car park, row on row of white trucks emblazoned with black lettering on fluorescent panels, orange flags on whip antennae adorning each and every cab. I was to stay with a friend, a journalist posted to regional WA, and he picked me up in a company car, which was of course another white Toyota Land Cruiser. As we got in the truck, he threw his recently-acquired Akubra – purchased to help him fit in after his move from ‘back East’ – on the back seat. We pulled onto the highway and a massive ore train began to rumble past on the horizon.

My friend began to explain that Karratha was far more “cosmo” than he had expected, a result of the long-tailed mining boom. The buildings whizzing by certainly testified to that fact – they were all in a post-modernist style, with loads of dark grey and white and a boat and trailer alongside the white ute in front of what seemed like every second house. As we pulled into the driveway my friend commented that the house was rated to survive a category 4 cyclone, so perhaps I really wasn’t in Kansas anymore.

Here was my first reminder that the rising tide of the mining boom may not have lifted all boats equally. The sharehouse I was staying in was owned by my hosts’ employer. They had had to purchase the house because the rents in Karratha had climbed so astronomically that the salary for a tertiary-educated journalist was no longer large enough to service it. The rent was now pegged to the occupants’ salaries, not the market. Karratha might have a set of luxury apartments in the Pelago and a brand new cultural center in the heart of town, but it is all just a stark reminder of how easily disadvantage can be rendered invisible. A rising tide is fine if you have a boat – but you can still drown in a flood of money.

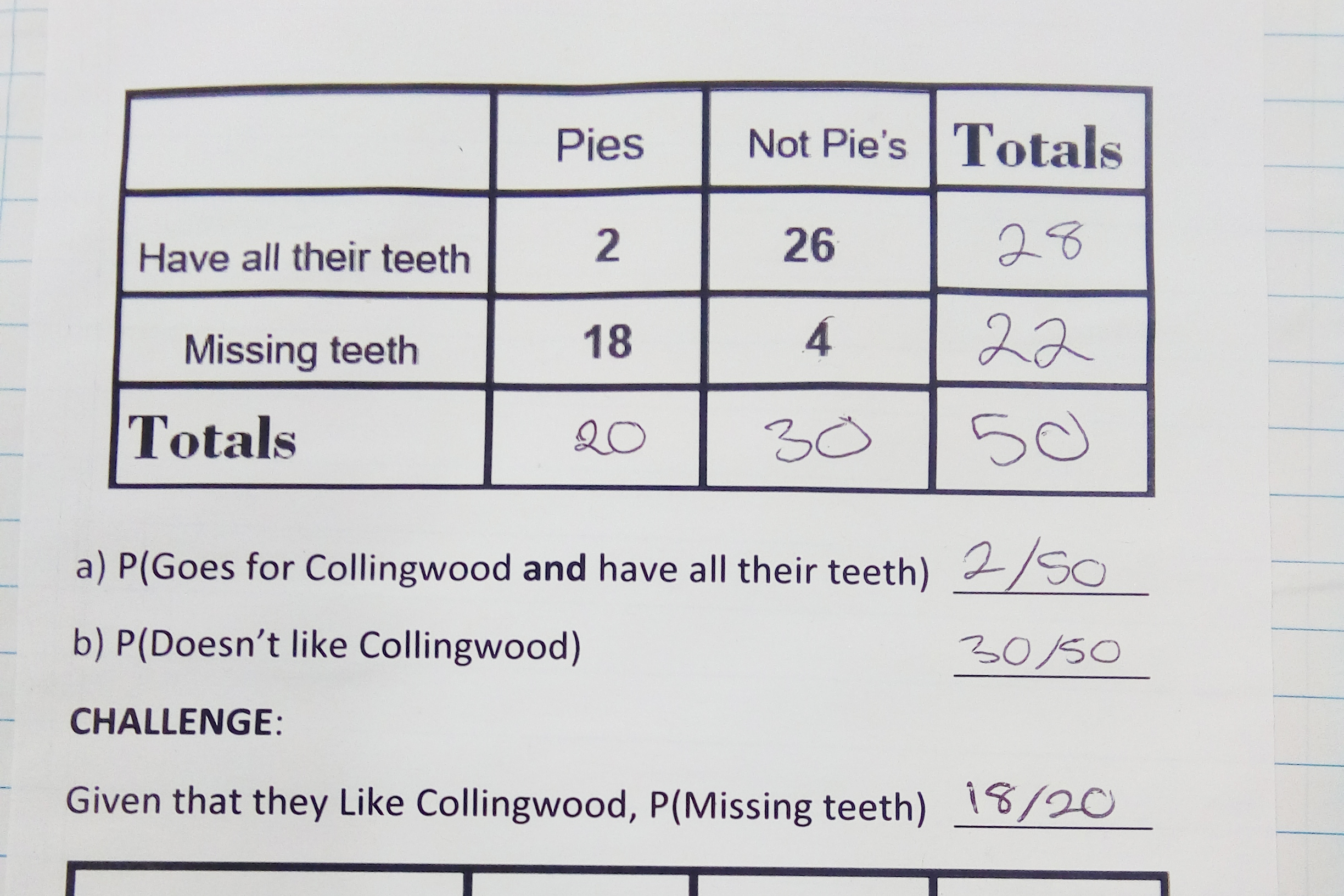

That night I ate at the Karratha Rec Club with another TFAer, Lorraine Moriarty. The Rec Club feels like a sign of what Karratha was like before the flood. It’s a long, low, cinder-block building with an ancient black ‘visitors’ book in lieu of the kind of automated sign-in I’m used to in city RSLs. Lorraine had been at Karratha High School that day, visiting Associates’ classrooms. She’d seen David Hennessy, a first year Associate, teaching his Maths class. She showed me a photo of a worksheet he’d designed which used AFL as the basis of a probability problem.

She’d also been making ‘pros and cons’ lists in another Associate’s class – Jess Baikie, who teaches Humanities. Apparently one of the students had decided to list the pros and cons of having a mullet. She couldn’t remember anything on the ‘pros’ list but the student had gleefully exclaimed when called on that there were “no cons to having a mullet miss!”

Shortly afterwards the West Coast vs. Essendon game came on one of the two flatscreens in the club. As the Bombers pulled in front, the lone Essendon supporter – clearly a FIFO – got more and more excited in the sea of veteran Karrathans turned sour, though in a friendly enough way. Just like back East.

By the third quarter the star attraction was no longer the footy, but the women’s darts competition that slowly took over the other half of the Rec Club. A dart part salesman showed up and began to display his wares on the pool table. One team that seemed to be made up of indigenous women sported a team uniform that proclaimed them to be the ‘black pearls’. Lorraine quickly melted into the crowd and began making friends.

After the Bombers dispatched the Eagles I caught a cab home. The driver was a Somali refugee with an Engineering degree. He’d come back to Karratha from Perth chasing the prophesied return of the boom, hoping to get his old job back. It’s easier to get a job in Oil & Gas if you’re in Karratha. He told me that he was happy that we’d placed teachers in the schools here, that he wished we’d place more, and that it was such a challenge getting indigenous kids to stay in school, because he saw them wandering the streets during the day. The cab – dispatched remotely by a call center in Perth – cost twice as much as a Melbourne cab.

The next day was my school visit. Along with two members of the state team, the Principal, Jennifer McMahon, and a potential funder, I had the privilege of watching Lilli Morgan teach her Humanities class. Lilli’s teaching was so full of energy, and after only six months in the job she’d clearly brought the kids on side. Her rapport seemed effortless – which can only mean it has taken immense effort to achieve.

The class watched a video about landing on Mars before moving out into the large adjoining hall to sketch out their own Mars colony in teams of three. I sat with a couple of the groups and talked to the kids about how their colonies would look. Their imaginings of Mars were very like my imaginings of Karratha – flat, red, and remote – but they described the landscape with familiarity. Under their pens Mars had parks and walkways and schools and hospitals. One girl explained to the class that the main trade good would be weapons, to which Lilli snorted in disbelief: “What for!?” “Hunting!” said the girl. “Hunting what?” “… Cows!”

On the walk back to the staffroom, Jennifer explained that the same social and cultural forces that draw the miners and their money out of the town like a receding tide also affects teachers (and the journalists, I knew from my hosts). The town invested most of the money it gained from the mining boom through the ‘Royalties for Regions’ program into ‘cosmo’ developments like the Pelago and the Arts Centre to try and build a community that teachers like Lilli and Jess and David might stay in. From the look of the town center – which could be an outer suburb of Melbourne or Sydney or Perth – it’s working.

We got back to the staffroom and had a Q&A with Lilli and Jennifer. Jennifer described the challenges of being a new teacher, which are as much behaviour management as they are content delivery. As someone who’s spent a lot of time teaching in tertiary classrooms I can only imagine how hard this must be. My sympathetic anxiety from unconsciously imagining myself in such a hostile classroom was only increased by Jennifer’s next statement – that it’s an article of faith amongst teachers that you “don’t smile ‘til April”.

We talked with the Associate Principal, who is helping to mentor the school leadership at Roebourne, 40km down the road – ‘just next door’ for a town where young migrants to the region regularly do a 4-hour round trip to the Port Hedland markets just for fun. Roebourne has a terrible reputation, so much so that the school no longer accepts external visitors, wary that the attention the school garners is more “disaster tourism” than a real effort to help. This pessimism was not reflected in the AP’s voice; with such a good relationship between the schools and the mentoring provided by Karratha SHS, he is upbeat about Roebourne’s students and their future.

Sitting alongside two representatives from the corporation considering funding the program, it’s a great reminder that help in a system as sprawling and complex as education is more than just looking at a school where things have gone wrong and figuring out how not to repeat the problem. Real change requires an investment of time and expertise and something more; relationships and trust.

I stayed for the weekend with my friend. On the Saturday I was treated to one more reminder of Karratha’s recent past: the six-weekly meat truck. Like a cleaner version of something out of Mad Max, this truck arrives at “Dreamers’ Hill” every six weeks, and sells all sorts of meat from its refrigerated trailer – beef, bacon, buffalo, camel. “Dreamers’ Hill” is so named because it’s where everyone dumps all the stuff they don’t need when they leave Karratha, because distance means it’s cheaper to sell for a loss and buy new wherever you’re going. As a final irony, it’s not a hill at all – just a parking lot near a roundabout. Another reminder of the difficulties of getting out of remote areas, and the ever-present ‘brain drain’. It was lined with cars – compact SUVs to massive Land Cruisers and Patrols – most of which have 200,000km or more on the dial because of the stupendous distances out here. Unlike a city car in stop-start traffic, those sorts of odometer readings aren’t a problem. People out here buy cars for different reasons – the 3.2L Turbo petrol engine in a particular type of Nissan Patrol being particularly prized for its robustness and resilience.

My last stop before the airport on Sunday is a small rise behind the town where there’s a lookout near a phone tower. You can see the whole town laid out before you and get a sense of how small it is, and how flat, and how abruptly it stops being a town and starts being wild, flat ground. Thirty minutes later I was through security and sitting on the plane. Once again, I was surrounded not by FIFOs but by family members departing for Perth after a weekend with loved ones. The FIFOs were on the arriving flights, sans high-vis after a weekend’s R&R in Perth.

As the plane banked over Karratha I could clearly see the patch of dirt on top of the hill where I had been standing just 45 minutes before. Reflecting on my whirlwind tour of the town, I kept coming back to the fact that the kids were ultimately like any other kids I’d ever met. They liked footy and dreamt of a life on Mars and dawdled and laughed and got distracted and showed off and wilted in the spotlight of the teacher’s attention. It was a reminder that disadvantage doesn’t conform to the images of starving children on another continent, it doesn’t accrue to obvious divisions in race and class and region (except, of course, when it does) and it can exist in a place where there’s a boat in every driveway. Disadvantage can be invisible, it can hide in plain sight, and we can be dazzled by other people’s privilege just as much as by our own.