Skip to:

- Give Today

- Contact Us

- Media

- Search

News & Stories

Leadership Development Program

Undergraduate Teaching Program

Common search terms

This is the story of how teaching taught me to let go.

It’s a simple idea, but one I have never quite been the master of. As a child I tried to please all of my friends at once. A friend was mad at me? The world was over. Teenage me fought for doomed relationships, and university me fawned over tutors, careful never to get on anyone’s ‘wrong side’. In the workplace I tried to be the most pleasant person around, always helpful but never too assertive.

I had an inane need to satisfy those around me. My joy came from pleasing others, and I didn’t like it when people didn’t like me. If they disliked me, I had to try and fix it. I was a dove.

Then I started teaching.

When you meet 100 raging teenagers all at once and have to try teach them things, at least one of them, if not several, are bound to dislike you. Throughout the tumultuous journey that is my first year of teaching, I have gradually made peace with this reality. And without a doubt it’s been my biggest and most beautiful ‘lesson’.

At first I cared so much. Too much. When a student told me my class was boring or that they hated me, I struggled not to take it personally. I would ask myself: What can I do better? What can I change? When a kid wagged my class I’d lie awake at night thinking, where have I gone wrong?

When students made inappropriate comments about or towards me, I told myself it was my fault. Should I wear different jeans tomorrow? Should I yell at them like I want to, or will that make them hate me? The questions were all about me; how could I fix the situation and keep the students happy? It was a futile cycle of trying (and failing) to please all of my kids, to the detriment of my wellbeing.

Halfway through the year I cracked. I walked into a wildly inappropriate conversation that a group of students were having, just as one of them was making a vulgar, objectifying comment about me. I was so shocked that I walked away, unwilling to cry in front of them.

But then I broke. The issue was brought to the leadership team’s attention, and some uncomfortable restorative conversations with the involved students followed.

After that, school was painful for a while. Sometimes the kids wagged. They avoided eye contact with me; one just pretended I didn’t exist. But their projected hatred of me opened my eyes. I finally began to let go. I started to feel less pained, even when they lashed out more.

They were mad that their behaviour had been called out, and it was so clear that the issue was about them, and their own problems they were struggling with. They ‘hated’ me, but that was okay. Sometimes students are going through their own things, and you just have to let go of the negative feelings they have towards you. Things have gotten better, and the kids even politely address me from time to time. We’ve come a long way.

The questions I used to ask myself are changing. Now it’s not about what I’m doing wrong, or blaming myself. Instead, it’s about what’s going on with that student to make them act like this. How can I support this kid to help them with what THEY are going through?

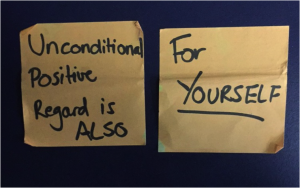

We have to be so forgiving as teachers, but above all, forgiving of ourselves. I can pinpoint the exact moment I truly accepted this; it was on a particularly tough day with my Year 9s. I was rushing by my friend Elise’s desk, which is usually so messy you can’t see the bottom layer, but today was oddly clean. Two post-its stuck to her desk caught my eye, and I stopped. The notes said simply: ‘Unconditional positive regard is also for yourself.’

The hard truth of the statement hit me all at once. So often we are encouraged to show unconditional positive regard (UPR) to our students, to other people, accepting and respecting them without judgement. But before we can do that, we must show UPR to ourselves. Only then can we let go.

I’ve realised that if I can’t let go, I can’t let so many good things in. This has applied not just to school, but so many other aspects of my life.

I’ve realised that things aren’t always about my response, about me solving them peacefully. I am not responsible for fixing everything that is broken.

I’ve realised that letting go doesn’t mean you don’t care anymore. Sometimes you have to stop trying to force others to care. Maybe they will come around, maybe they won’t.

Letting go is an idea that we as humans evoke often. We all know there are times we need to let go because it hurts more to hold on. But you can’t magically teach yourself to let go, even if you know that’s what you should do. You have to learn it from somewhere else. And I got it from teaching. I’m certainly not an expert, but I’ve definitely become better at it. For that win, I am forever grateful. My job is really quite remarkable.