Teachers are in a unique position to help their students grow into compassionate, humane young adults, able to create and support a diverse, rich and kind society. We have the opportunity to role model, to discuss, to provide counter-examples against biases and to develop critical and ethical thinking capabilities in our students. I am an ardent believer of this idea.

And yet, when I look and listen around me, I feel incredibly tired, weighed down by the enormity of the struggle we still face.

There is so much ground our society has to cover to become a compassionate one.

We still see horrifying rates of gendered violence in our country, a national crisis of respect that we still seem unable to honestly evaluate and address, despite the terrifying monotony with which it dominates our front pages.

We see a commercial for personal grooming products, basically asking men to not be awful to each other and those around us, and we launch an insanity of vitriolic drivel about ‘man hating’, ‘misandry’ and other absurdities.

A prominent indigenous media figure makes a reasoned explanation of why she doesn’t want to celebrate Australia Day in its current form. Cue the racist, ignorant and dehumanising responses.

A colleague uses homophobic language in the office, without even registering that it is derogatory (and explicitly against school and department policies).

And now it seems that we are having to genuinely explain why being a neo-Nazi is not okay. This one I saw first hand, attending the anti-Nazi counter-rally at St Kilda beach in early January. I heard directly the racist slogans, I heard the homophobia and misogyny being sprayed out of the mouths of the tremendously pale, Y chromosome-heavy group opposing us. I saw the aggression, the desire for violence against those they disagreed with. And yes, I saw the Nazi salutes and goose stepping. If it looks like a duck, if it quacks like a duck…

(On a satisfying coincidental side note, as I was writing this paragraph, the 2018 Frank Turner song 1933 came onto my shuffled playlist – very apt.)

It’s almost too much to deal with.

Is the battle for compassion and kindness too hard?

Do we simply have to roll over and accept that our ‘better angels’ have lost?

The fact that I have gone to the effort of writing this should give you some indication of what I think the answer is. While we have so much negativity around us all, I firmly believe that there is genuine hope, genuine opportunity to make change. Genuine potential to create a more compassionate society, starting with teachers and their students.

This challenge is a genuinely overwhelming, amorphous, multi-faceted beast. There are no silver bullets, no simple solutions that will magically fix the problem. Yet there are acts, both small and large, that can make a difference, that will move us toward a more compassionate and kind society.

I believe that education can be at the forefront of this and that there is a moral imperative for us to be drivers of this work. Our students become the adults that inherit the maintenance and development of our society. If they can recognise the value of respect and compassion, change is impossible to stop.

So after all that slightly melodramatic verbosity, what do we do?

Model respect at all times

This one should be a no-brainer, really. Teachers have a professional obligation to show and model respect for all people throughout their work. Nevertheless, I think it should be highlighted explicitly. The power of modelling and of student mimicry of behaviour is significant and is a way to constantly provide reinforcement for the kind of empathetic, compassionate actions we want to see in our young people. Change always needs to start with yourself.

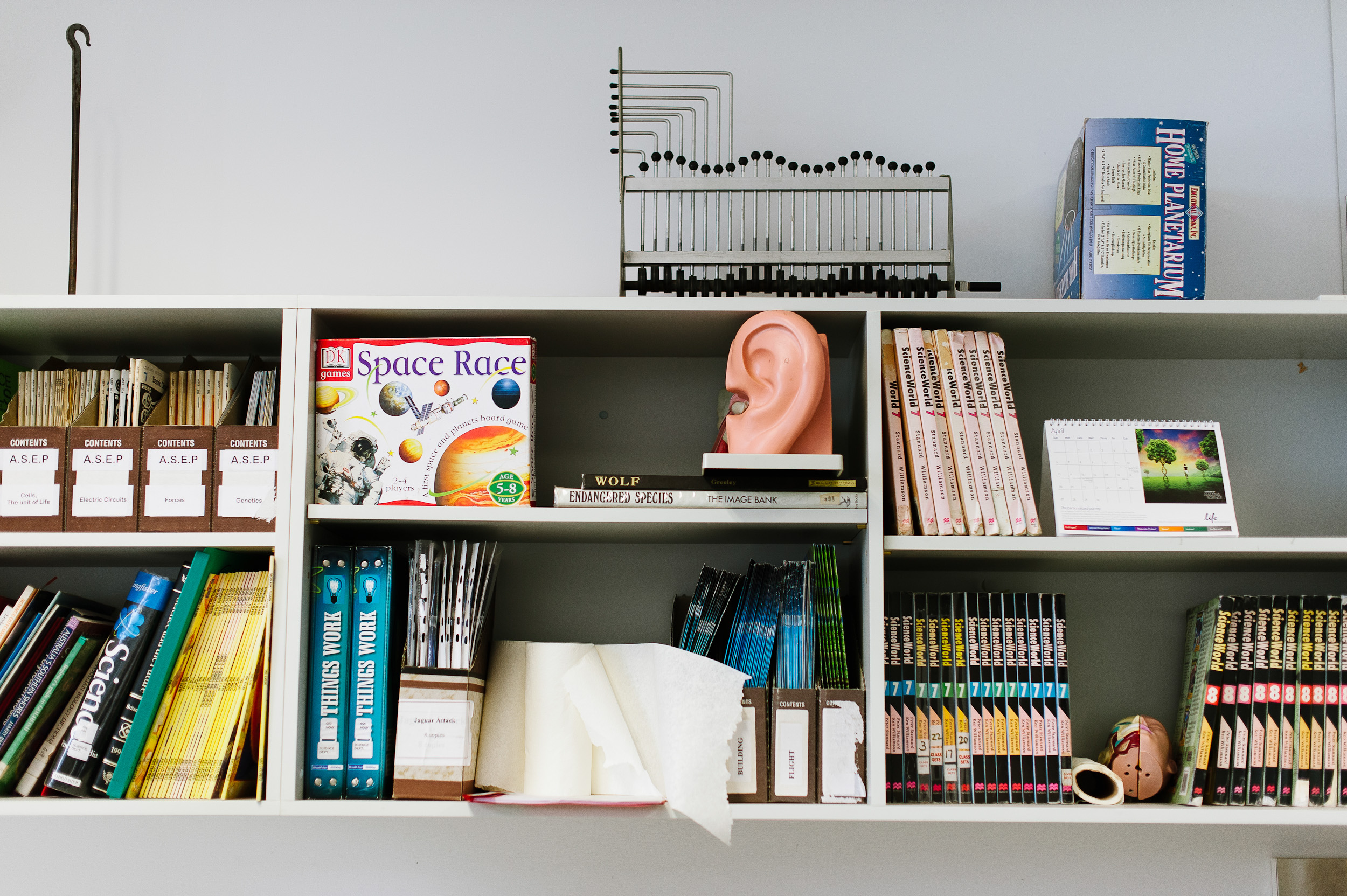

Teach the Capabilities

The curriculum is not just about content knowledge, or even subject-related thinking skills. We have a range of ‘capabilities’ that are explicitly mapped out in our mandated curriculum documents that can help us develop the social and emotional capacities of our students. These are the often maligned ‘soft skills’, yet there is nothing soft about them. In practice, they are the key things we talk about when we describe education as a process of helping young people develop themselves into well-rounded adults.

Ethical, Personal, Social and Intercultural capabilities in the curriculum provide a framework for designing learning activities that engage students to think about their community and to begin the process of building the skills to act with respect and compassion. They can and should be explicitly taught to students throughout the years of schooling and can be integrated into instructional programs and projects across any learning area.

Include diversity and the ‘Them’

The next couple of suggestions draw fairly heavily on Robert Sapolsky’s exceptional book Behave: The Biology of Humans at out Best and Worst. The book is a phenomenal read, not least for the chapter titles such as “Adolescence; or, Dude, Where’s My Frontal Cortex?”. It will totally change your perception of humans and how and why we behave the way we do. (If you’re ever in court, try to make sure the judge is well-fed.)

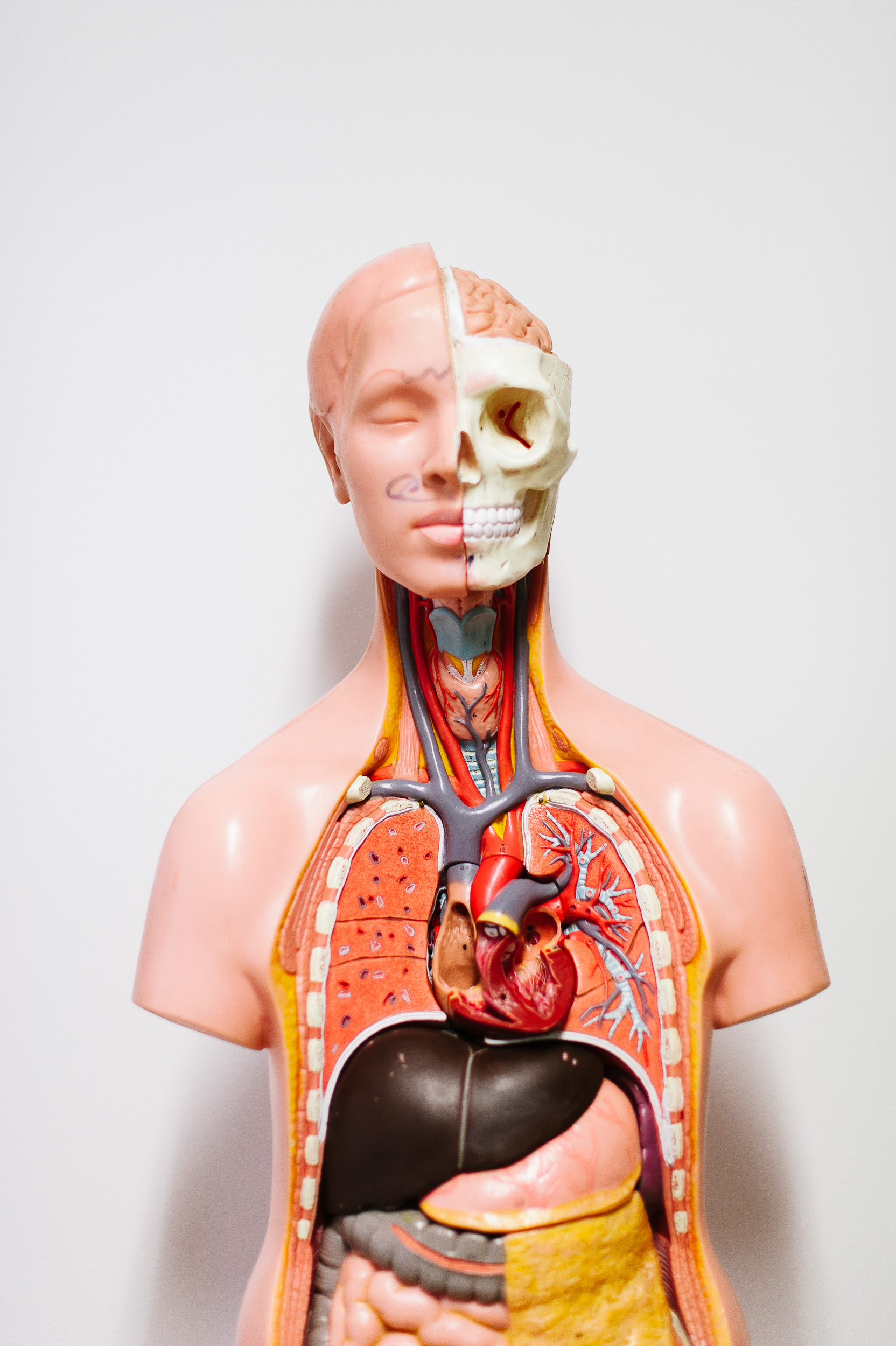

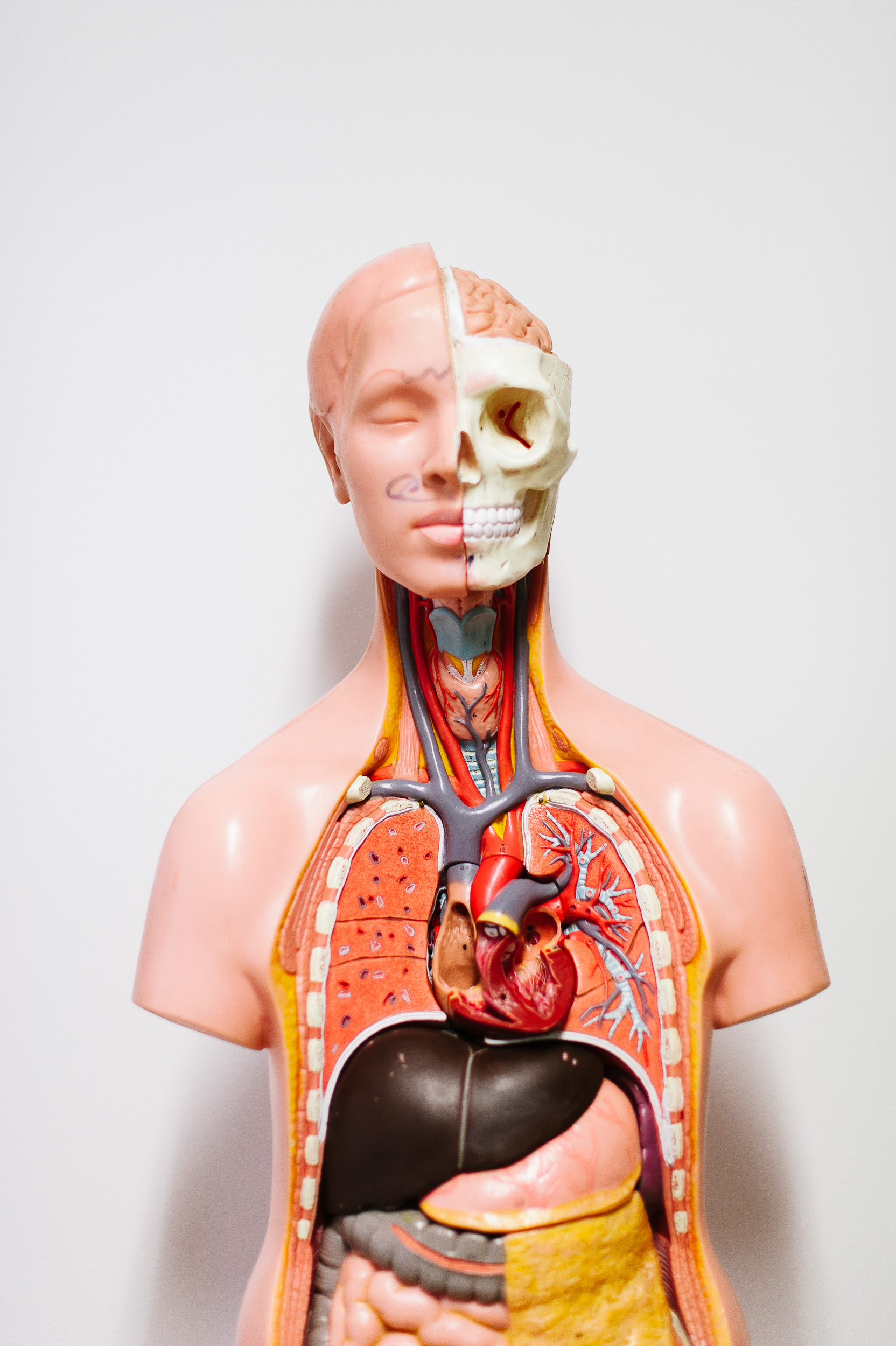

Human beings are incredibly skilled at creating ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ groups, often using unbelievably arbitrary and inconsistent traits. We also do it incredibly quickly for those who appear to be outwardly different, activating the amygdala (the primitive and fear-driving part of the brain) within milliseconds of seeing such a face. Implicit association tests reveal with dark clarity the inherent biases we all carry against outgroups. Unfortunately, we are hardwired to split the world into Us and Them, and make decisions based on that arbitrary divide.

A case in point is the oft-cited ‘cuddle hormone’ oxytocin, famed for promoting pro-sociality and monogamy (at least in voles anyway…). Turns out, oxytocin has a very Us/Them-dependent double-edged sword: if you increase oxytocin in someone’s brain, you do indeed see more pro-social behaviour, provided they are around, or can act on behalf of, what they see to be their Us group. But if you introduce a Them group instead, the person will exhibit increased anti-social and punitive behaviours! Not so cuddly now, hey?

The perception of outgroups and Them as negative, disgusting or outright hostile is well-documented in research and cultural works throughout history. Primates and other animals also demonstrate such Us/Them bias, the difference with humans in particular being that we have added entire layers of complexity through culture, religion and nationalism, among other fun factors.

But that same body of research says that we can do something about this with relatively simple acts.

Consistent, well-structured exposure to any Them group over time decreases biases and negative behaviours against them, as we are more able to allow our cognitive frontal cortex time to think and fight against the knee-jerk reactions of our more primitive systems. We begin to experience the fact that They are the same as Us in most ways that matter, and then begin to have very different rationalisations. Thinking then moves from an essentialist focus (that all members of a group having an innate ‘essence’, which is usually negative) to an individualist one (in which we are more able to identify the variability and individuality of those in a Them group, in the same way we can for those in our Us group).

By making a conscious effort to include information, perspectives and knowledge from a range of cultures and groups of people and by making sure that students from all backgrounds have the chance to show their cultures and to engage with each other, the Us/Them barriers begin to fall away. Sharing a common goal is a brilliant way to do this.

For our school and for many of our boys, soccer is that common goal. Our soccer teams contain young men born in Australia (both indigenous and non-indigenous), Afghanistan, Burma, Pakistan and multiple other places: a myriad of potential Thems. Yet, the common goal of winning and excelling together trumps all of that and helps these young men to humanise and act positively towards those who superficially seem alien to them.

Teach students and teachers the psychology of bias and prejudice

Following on from the above, we can’t fix what we don’t know or can’t recognise. The obvious challenge with decisions and anti-social behaviour driven by implicit bias is its implicity by very nature and, thus, it’s hard to detect. (It might even potentially be somewhat hidden from the person themselves.)

Teachers should slowly and carefully guide our students to explore and expose their implicit biases. Those initial responses should not define how we react to and treat each other. Teachers can help them understand how knee-jerk, neurologically primitive responses from our amygdala can be overridden.

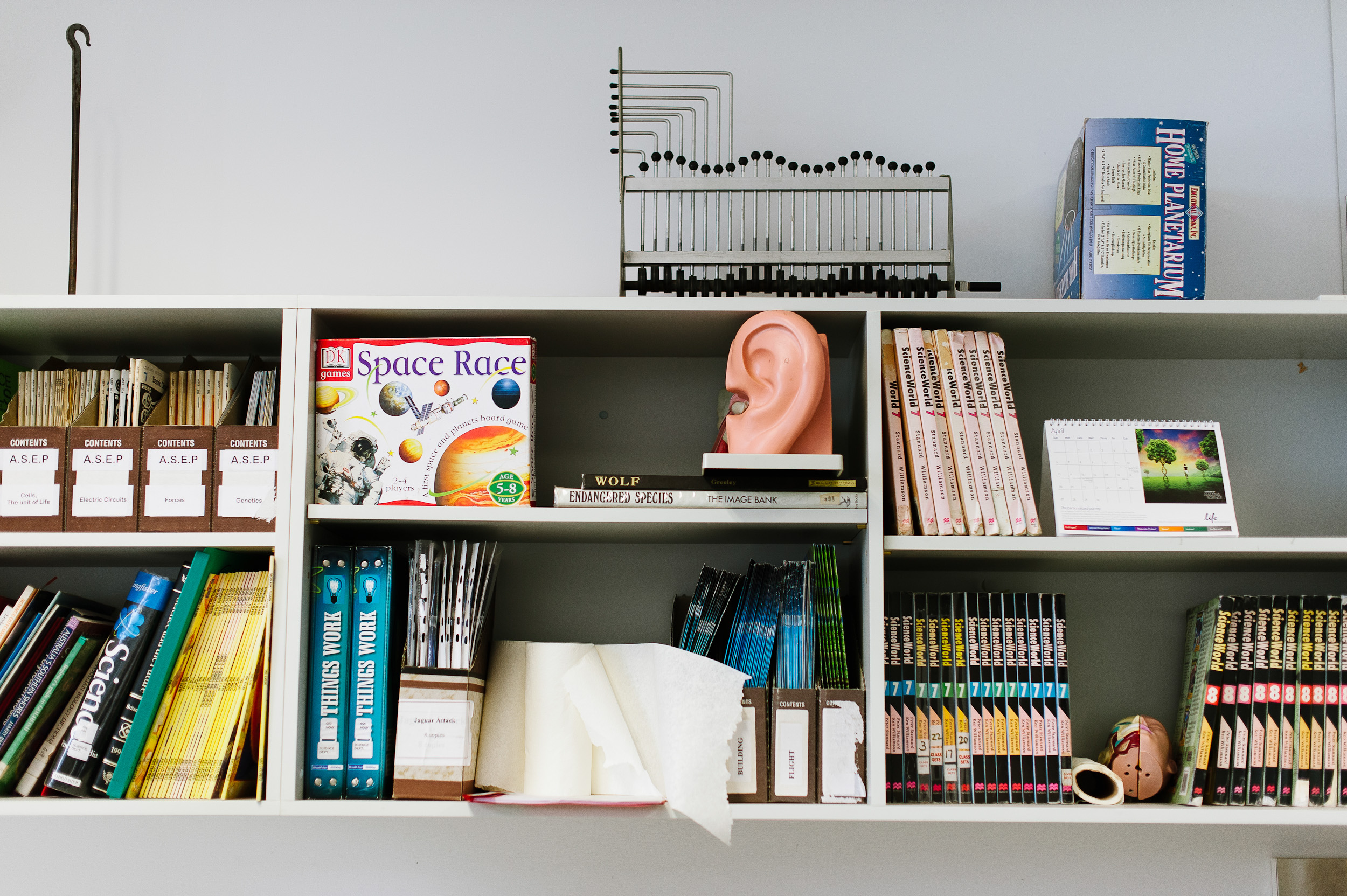

We can create Science, humanities and ethics programs that allow students to understand their brains. We can create and embed programs that teach how brains develop, and how our environment, experiences and life histories can lead to unfounded assumptions and prejudices (such as against women, against other nationalities, or against religions). We need to acknowledge and work to overcome those prejudices so that we can be truly compassionate and kind not only to Us, but also to everyone else.

All of this may seem like an enormous and unreasonable load to ask the still-developing shoulders (and, more importantly, the developing frontal cortex) of our young people and children to bear. Yet, they will not need carry this load alone. Now more than ever, they need us, their teachers.

They need rational, emotionally intelligent adults to help them navigate their development and to help them genuinely understand themselves, each other and the world around them. Teachers and schools as a whole are uniquely placed to work with young people and to support their families in this work. As I’ve said before, we have a vital role for showing students how to live a life of compassion and respect for all.

We need to provide them with the nuanced cognitive and emotional tools to live well and to continue to improve our society. To return to Frank Turner: you can’t fix the world if all you have is a hammer.